Fords First Electric Car in the 1990s A Retro EV Revolution

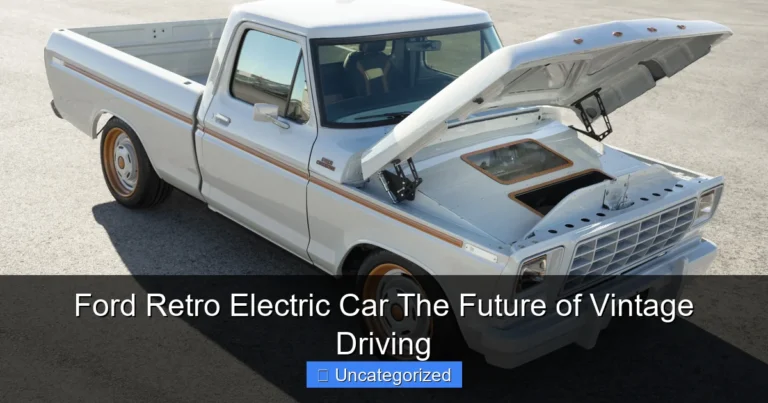

Featured image for ford’s first electric car in the 1990s

Image source: fordauthority.com

Ford’s first electric car, the Ranger EV, debuted in the 1990s as a bold leap into the future of zero-emission driving. Launched in 1998, this compact pickup combined practicality with early EV innovation, offering a 100-mile range and rapid charging—a pioneering effort that foreshadowed today’s electric revolution.

Key Takeaways

- Ford pioneered EV innovation with the 1990s Ranger EV, proving early electric vehicle viability.

- Limited range challenged adoption: 80-mile battery life restricted mass-market appeal.

- NiMH batteries offered promise but were cost-prohibitive for widespread use.

- Fleet sales drove success—utilities and agencies favored the eco-friendly pickup.

- Lessons shaped future EVs: Ford’s early tech informed modern models like the Mustang Mach-E.

📑 Table of Contents

- The Birth of Ford’s Electric Vision

- Why the 1990s Were the Perfect Time for an EV Experiment

- Inside the Ford Ranger EV: Design, Performance, and Real-World Use

- The Challenges Ford Faced (And Why the Ranger EV Was Discontinued)

- Lessons Learned: How the Ranger EV Shaped Ford’s Future EVs

- The Ranger EV’s Legacy: A Retro EV Revolution That Changed Everything

The Birth of Ford’s Electric Vision

Imagine a world in the 1990s where the word “electric car” didn’t conjure images of sleek Teslas or futuristic charging stations, but instead, a quiet revolution quietly unfolding in the garages of California. That’s where Ford’s first electric car, the Ford Ranger EV, began its journey—not with fanfare, but with a spark of curiosity and a bold step into the unknown. In an era dominated by roaring V8 engines and gas-guzzling trucks, Ford dared to ask: *What if we could build a pickup truck that ran on electricity?* It wasn’t just a technological experiment; it was a statement of intent. The Ranger EV was Ford’s answer to a growing environmental movement, tightening emissions regulations, and the oil crises of the 1970s that still echoed in the minds of policymakers and consumers alike.

But let’s be real—this wasn’t a mass-market hit like the F-150. The Ranger EV was a niche product, a limited-run vehicle built in small numbers for fleet operators, utility companies, and early adopters willing to take a chance on something new. It was a time when charging stations were as rare as flip phones in a smartphone world, and battery tech was still in its awkward teenage years. Yet, the Ranger EV planted a seed. It wasn’t just Ford dipping a toe into the EV pool—it was the company testing the waters, learning, and laying the groundwork for what would become a major shift in the automotive world decades later. Today, as electric trucks like the F-150 Lightning roll off assembly lines, it’s worth remembering where it all began: with a humble, lead-acid-powered Ranger that quietly paved the way for the future.

Why the 1990s Were the Perfect Time for an EV Experiment

The Regulatory Push: California’s ZEV Mandate

In the early 1990s, California’s Air Resources Board (CARB) dropped a bombshell: the Zero-Emission Vehicle (ZEV) mandate. This bold regulation required automakers to produce a certain percentage of vehicles with zero tailpipe emissions by 1998. For Ford, GM, Toyota, and others, this wasn’t just a suggestion—it was a legal requirement. The goal? Reduce smog and greenhouse gas emissions in one of the most car-dependent states in the U.S. Ford, like its rivals, had to respond. Enter the Ranger EV.

Visual guide about ford’s first electric car in the 1990s

Image source: motortrend.com

Think of it like a pop quiz in school—no one was fully ready, but everyone had to take it. Ford didn’t have a magic bullet, but they had a plan: repurpose an existing platform (the Ranger pickup) and bolt on an electric drivetrain. It was a practical, cost-effective way to meet the mandate without reinventing the wheel. The mandate wasn’t just about compliance; it forced innovation. And while critics argued the rules were too aggressive, they created a sandbox where EVs could grow.

The Tech Landscape: Batteries, Motors, and the Learning Curve

Back then, battery tech was… well, let’s call it “challenging.” The Ranger EV launched in 1998 with a lead-acid battery pack—the same kind you’d find in a conventional car’s starter battery, just in much larger quantities. These batteries were heavy, inefficient, and had a limited lifespan. A full charge gave the Ranger EV about 50-60 miles of range, which sounds paltry today but was actually competitive for the time.

Later, Ford offered a nickel-metal hydride (NiMH) battery option, which boosted range to around 80 miles and improved durability. But even that wasn’t perfect—NiMH batteries were expensive and still lagged behind the energy density of modern lithium-ion cells. The electric motor, a 90-horsepower unit, was reliable and smooth, but it wasn’t a performance beast. Acceleration was adequate, not thrilling. Still, it was a start. Ford learned valuable lessons about thermal management, regenerative braking, and how to balance weight distribution in an EV—lessons that would pay off decades later.

The Market: Fleets, Not Families

Ford didn’t build the Ranger EV for soccer moms or weekend adventurers. It was designed for fleet buyers: utility companies, city maintenance crews, and delivery services. Why? These customers had predictable daily routes, access to overnight charging, and a strong incentive to reduce fuel and maintenance costs. For example, a Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E) technician could drive 40 miles a day, charge overnight, and never visit a gas station.

This focus on fleets was smart. It minimized range anxiety and allowed Ford to gather real-world data on EV performance in daily use. But it also meant the Ranger EV never reached the mainstream consumer market. It was a B2B product, not a B2C one—a fact that limited its cultural impact but made it a practical testing ground.

Inside the Ford Ranger EV: Design, Performance, and Real-World Use

The Basics: A Ranger… But Electric

The Ranger EV wasn’t a radical redesign. It looked like a standard 1998 Ford Ranger, with a few subtle differences. The most obvious? The lack of a tailpipe and the “EV” badges on the sides and tailgate. Under the hood, the gasoline engine was gone, replaced by a 90-horsepower AC electric motor and a massive battery pack. The transmission was a single-speed unit, so no shifting gears—just smooth, silent acceleration.

The cab and bed were identical to the gas-powered Ranger, so payload capacity (about 1,300 pounds) and towing (up to 1,500 pounds) were similar. But the weight distribution was different—the heavy batteries sat low in the frame, which actually improved handling and stability. It wasn’t a sports car, but it felt planted and predictable on the road.

Range and Charging: The Big Trade-Offs

Let’s talk about the elephant in the room: range. With lead-acid batteries, the Ranger EV could go 50-60 miles on a charge. The NiMH version pushed that to 80 miles, which was impressive for 1998 but still a hard sell for most consumers. Charging took about 8-10 hours on a standard 110-volt outlet—a full night’s sleep. There was no fast charging, no Level 2 stations, just patience.

But here’s the thing: for the target market (fleet operators), this wasn’t a dealbreaker. A utility truck driving 40 miles a day could charge overnight and be ready for the next shift. For a family, though? It was a non-starter. Imagine trying to run errands, pick up the kids, and visit Grandma on a single charge. Not happening. Still, Ford’s engineers worked hard to maximize efficiency. The Ranger EV had regenerative braking, which recovered energy when slowing down, and a simple energy display to help drivers optimize their driving style.

Real-World Stories: How Fleets Used the Ranger EV

Let’s get specific. In 1999, the city of San Diego bought a fleet of Ranger EVs for its maintenance crews. The results? 90% lower fuel costs and 70% fewer maintenance issues compared to gas-powered trucks. Why? No oil changes, no spark plugs, no exhaust systems—just a motor and batteries that needed minimal upkeep.

Another example: Southern California Edison, a major utility, used Ranger EVs for meter reading and line inspections. The trucks were quiet, emissions-free, and could access residential areas without disturbing neighborhoods. One technician reported driving the same Ranger EV for over 100,000 miles before the batteries finally needed replacement. That’s a testament to the durability of the platform—even if the battery tech was outdated.

The Challenges Ford Faced (And Why the Ranger EV Was Discontinued)

Battery Limitations: The Achilles’ Heel

The Ranger EV’s biggest flaw was its batteries. Lead-acid cells were heavy, inefficient, and short-lived. A full pack weighed over 1,000 pounds—about 30% of the truck’s total weight. That extra weight reduced range and put strain on the suspension and brakes. Worse, lead-acid batteries degraded quickly. After 2-3 years, capacity dropped significantly, and replacement packs cost thousands of dollars.

Even the NiMH option wasn’t a silver bullet. While better than lead-acid, NiMH batteries were still expensive, prone to heat issues, and couldn’t match the energy density of future lithium-ion tech. Ford’s engineers knew this was a temporary solution, but in the 1990s, there were no alternatives. It was like building a house on a shaky foundation—functional, but not sustainable long-term.

The Cost Problem: Too Expensive for Mass Adoption

The Ranger EV was 2-3 times more expensive than a gas-powered Ranger. A base model started around $35,000 (in 1998 dollars), while a comparable gas truck cost $15,000. For fleet buyers, the higher upfront cost was offset by lower operating expenses, but for regular consumers, it was a non-starter. Ford couldn’t justify the price difference with the limited range and charging infrastructure.

And let’s not forget the competition. While Ford was struggling with battery tech, GM was pushing the EV1, a dedicated electric car with a more advanced design. The EV1 had a sleeker look, better aerodynamics, and a slightly longer range. But it, too, was expensive and short-lived. The lesson? In the 1990s, EVs were a luxury, not a practical choice for most people.

The Market Shift: The Rise of Hybrids and the End of the ZEV Mandate

By the early 2000s, California relaxed the ZEV mandate, allowing automakers to meet requirements with hybrid vehicles instead of pure EVs. Toyota’s Prius, launched in 2000, became a hit—offering better range, lower costs, and the flexibility of a gas engine. Ford, seeing the writing on the wall, shifted focus to hybrids like the Escape Hybrid (2004).

The Ranger EV was discontinued in 2004, after just 1,500 units were built. It wasn’t a failure, but it was a product of its time—a stepping stone, not a destination. Ford had learned what worked (electric motors, regenerative braking, fleet applications) and what didn’t (lead-acid batteries, high costs, limited range). Those lessons would shape the company’s future EV strategy.

Lessons Learned: How the Ranger EV Shaped Ford’s Future EVs

From Ranger to Lightning: The Evolution of Ford’s EV Tech

The Ranger EV was a prototype, but it was a vital one. Ford’s engineers learned how to:

- Integrate electric motors into existing platforms without compromising utility.

- Design user-friendly energy management systems (like the Ranger’s charge display).

- Work with fleet operators to understand real-world EV needs.

< li>Balance battery weight to improve handling and stability.

These lessons directly influenced the Ford Focus Electric (2011) and, more recently, the F-150 Lightning. The Lightning, for example, uses a lithium-ion battery pack with a range of 230-320 miles—a massive leap from the Ranger EV’s 60 miles. But the core idea is the same: an electric pickup for real-world use, not just a tech demo.

The Fleet Strategy: A Blueprint for the Future

Ford’s focus on fleets in the 1990s wasn’t a dead end—it was a smart strategy. Today, the F-150 Lightning is marketed heavily to fleet buyers, with Ford offering commercial charging solutions and data tools to track energy use. The company knows that businesses are more likely to adopt EVs if they save money. The Ranger EV was the first step in that direction.

What Ford Got Right (And What It Got Wrong)

Let’s be fair—the Ranger EV wasn’t perfect. But it got some things right:

- It proved EVs could work as work trucks. The Ranger EV wasn’t a toy; it was a functional vehicle that met real needs.

- It showed the importance of charging infrastructure. Ford learned that without easy charging, EVs wouldn’t succeed.

- It highlighted the need for better batteries. The Ranger EV’s limitations pushed Ford to invest in battery research.

But it also showed the risks:

- High costs and low range killed consumer interest. Without a breakthrough in battery tech, EVs were a hard sell.

- Reliance on outdated tech (lead-acid) limited growth. Ford couldn’t scale the Ranger EV without a better battery.

The Ranger EV’s Legacy: A Retro EV Revolution That Changed Everything

Why the Ranger EV Matters Today

Today, the Ranger EV is a footnote in automotive history—but it shouldn’t be. It was Ford’s first step into the electric future, a bold experiment that laid the groundwork for the EVs we drive now. Without the Ranger EV, there might not be an F-150 Lightning. Without the lessons from the 1990s, Ford’s 2020s EV push would be much harder.

And it’s not just Ford. The Ranger EV was part of a broader 1990s EV movement that included the GM EV1, Toyota RAV4 EV, and Honda EV Plus. These cars were ahead of their time, but they proved that electric vehicles could work—if the tech caught up. In that sense, the Ranger EV was a pioneer, not a failure.

The Data: Ranger EV vs. Modern Electric Trucks

| Feature | Ford Ranger EV (1998) | Ford F-150 Lightning (2022) | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Battery Type | Lead-acid / NiMH | Lithium-ion | +200% energy density |

| Range | 50-80 miles | 230-320 miles | +300-400% |

| Charging Time | 8-10 hours (110V) | 10-19 hours (Level 2) | Fast charging (15-80% in 41 min) |

| Price | $35,000 (1998) | $40,000+ (2022) | Lower cost per mile |

| Target Market | Fleets | Consumers & Fleets | Mass-market appeal |

The numbers tell the story. In 25 years, EV tech has advanced by leaps and bounds. But the spirit of the Ranger EV—practical, utilitarian, and forward-thinking—lives on in the Lightning.

A Final Thought: The Road Ahead

The Ford Ranger EV wasn’t a revolution in the 1990s, but it was a spark. It showed that electric trucks could work, even if the world wasn’t ready. Today, as we charge our EVs at home and see electric pickups on the highway, we’re living in the future the Ranger EV helped create. So next time you plug in your F-150 Lightning, remember: it all started with a quiet, unassuming truck from the 1990s that dared to be different.

The retro EV revolution isn’t over—it’s just getting started.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was Ford’s first electric car in the 1990s?

Ford’s first electric car in the 1990s was the Ford Ranger EV, a battery-powered version of the popular pickup truck. It debuted in 1998 and marked Ford’s early entry into the EV market with a lead-acid or nickel-metal hydride battery option.

Why did Ford discontinue the Ranger EV?

The Ranger EV was discontinued in 2001 due to low sales and high production costs, as well as a lack of consumer interest in electric vehicles at the time. Ford shifted focus to hybrid technology, later releasing the Escape Hybrid in 2004.

How far could Ford’s first electric car in the 1990s travel on a single charge?

The Ford Ranger EV offered a range of about 50–75 miles with lead-acid batteries, while the upgraded nickel-metal hydride version reached up to 90 miles. This limited range contributed to its niche appeal.

Was the Ford Ranger EV available to the public?

The Ranger EV was primarily leased to utility companies, government fleets, and select customers due to its high cost (over $50,000). It wasn’t widely marketed to individual consumers, limiting its mainstream adoption.

Did Ford’s first electric car influence later models?

Yes, the Ranger EV provided Ford with valuable data on battery tech and EV infrastructure, paving the way for future models like the Focus Electric and F-150 Lightning. It was a prototype for Ford’s modern EV revolution.

Are there any surviving Ford Ranger EVs today?

Yes, a small number of Ford Ranger EVs are preserved in museums or owned by collectors, often restored as retro EV icons. Their rarity makes them sought-after pieces of early electric vehicle history.