Thomas Edison Henry Ford Electric Car Revolution Revealed

Featured image for thomas edison henry ford electric car

Image source: s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com

Thomas Edison and Henry Ford’s 1914 electric car collaboration aimed to revolutionize transportation with a 100-mile range and home charging—decades ahead of its time. Their visionary partnership, though stalled by gas-powered competition, foreshadowed today’s EV revolution with uncanny precision. Discover how these titans pioneered the future of clean mobility.

Key Takeaways

- Edison and Ford partnered to pioneer early electric vehicles in the early 1900s.

- Affordable EVs were possible but halted by gas vehicle dominance and infrastructure.

- Edison’s battery tech laid groundwork for modern EV energy storage innovations.

- Ford’s assembly line could have revolutionized EV production if prioritized.

- Historical missed opportunity shows how timing shapes transportation revolutions.

- Legacy inspires today’s shift to sustainable, mass-market electric vehicles.

📑 Table of Contents

- The Forgotten Partnership That Almost Changed Transportation Forever

- The Vision: Edison and Ford’s Electric Dream

- The Electric Vehicle Landscape in the Early 1900s

- The Technical Side: Why Edison’s Batteries Failed

- Why the Project Failed (And What It Teaches Us)

- Legacy: How Edison and Ford Shaped the Future of EVs

- The Road Ahead: What Edison and Ford Teach Us About Innovation

The Forgotten Partnership That Almost Changed Transportation Forever

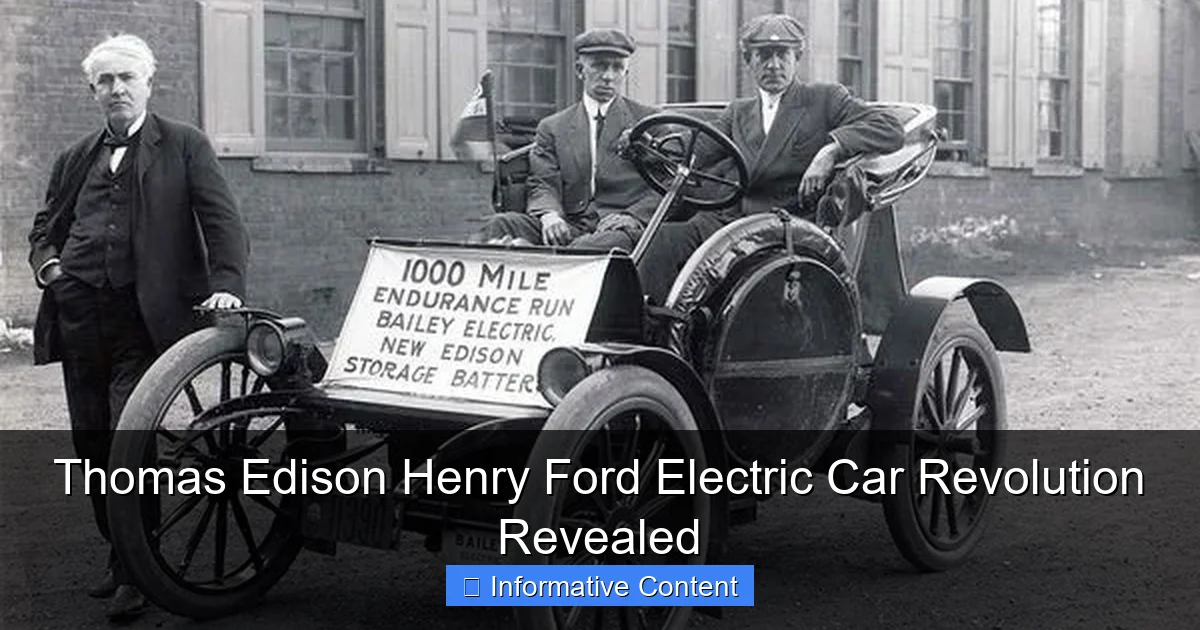

Picture this: It’s 1914, and the streets of Detroit are buzzing with innovation. Henry Ford’s Model T is revolutionizing personal mobility, making cars affordable for the average American. But what if I told you that at the same time, Ford and the legendary inventor Thomas Edison were secretly working on an electric car that could have changed the course of automotive history? It’s a story of ambition, friendship, and a vision that was decades ahead of its time. And yet, it’s a chapter in history that most of us know nothing about.

The Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project was a bold attempt to merge Edison’s cutting-edge battery technology with Ford’s mass production genius. Imagine a world where electric vehicles (EVs) became mainstream in the 1910s instead of the 2010s. No gas stations, no oil crises, no carbon emissions from tailpipes—just quiet, clean, and efficient electric cars rolling off assembly lines. While this vision never fully materialized, the partnership between these two icons remains a fascinating “what if” in the history of innovation. Let’s explore how it all happened, why it failed, and what lessons we can learn today.

The Vision: Edison and Ford’s Electric Dream

Two Geniuses, One Goal

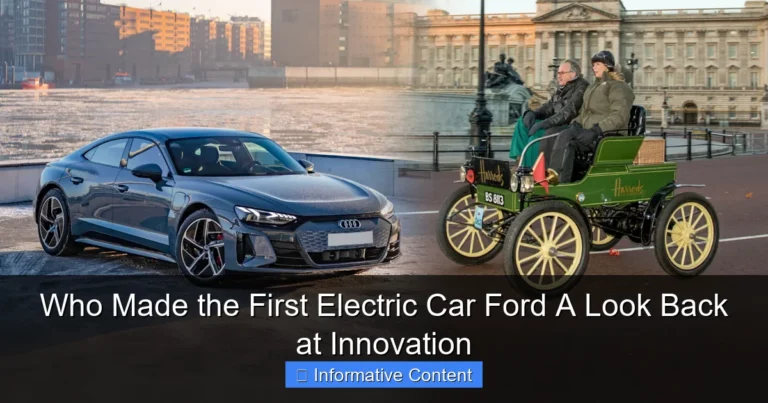

Thomas Edison and Henry Ford weren’t just business acquaintances—they were close friends. Ford often visited Edison’s lab in Menlo Park, and Edison even advised Ford on early engine designs. Their friendship was built on mutual respect and a shared belief that technology could improve everyday life. By 1912, Ford was producing the Model T, but he was also deeply interested in electric vehicles. At the time, EVs made up about one-third of all cars on the road. They were quiet, easy to operate, and didn’t require hand-cranking to start—a major advantage over gas-powered cars.

Visual guide about thomas edison henry ford electric car

Image source: leftfieldbikes.com

Edison, meanwhile, was obsessed with perfecting the electric car. He believed batteries were the future, not internal combustion engines. In 1901, he had developed the nickel-iron battery, which was more durable and longer-lasting than the lead-acid batteries of the day. But there was a problem: the technology wasn’t quite ready for mass adoption. So, in 1912, Ford and Edison struck a deal: Ford would design an affordable electric car, and Edison would supply the batteries. The goal? A $500 electric car that could travel 100 miles on a single charge—a revolutionary idea at the time.

The Challenges They Faced

Despite their enthusiasm, the Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project ran into serious hurdles. First, battery technology was still in its infancy. Edison’s nickel-iron batteries were an improvement, but they were heavy, expensive, and had limited range. A 100-mile charge might sound impressive today, but in 1914, it was a stretch. For comparison, the average Model T could go 200 miles on a tank of gas, and gas stations were becoming more common.

Second, the infrastructure for electric cars was almost nonexistent. Gasoline was cheap, abundant, and easy to transport. Meanwhile, charging stations were rare, and most homes didn’t have electricity. Even if Ford and Edison built a great electric car, most people couldn’t charge it. As Ford famously said, “The electric car is fine for the city, but the gas car is better for the country.” This divide—urban EVs vs. rural gas cars—would haunt the project for years.

Finally, there was the issue of timing. The Model T was already a massive success, and Ford was focused on scaling production, not experimenting with new technologies. As one historian put it, “Ford was busy changing the world with the Model T. He didn’t have time to wait for Edison’s batteries to catch up.”

The Electric Vehicle Landscape in the Early 1900s

A World of Electric Dreams

To understand why the Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project mattered, you need to see the EV landscape in the early 1900s. Back then, electric cars were far more common than gas-powered ones. In 1900, about 40% of U.S. cars were electric, 38% were steam-powered, and only 22% were gasoline. EVs were popular among wealthy urbanites—especially women—because they were quiet, clean, and easy to drive. No hand-cranking, no fumes, no loud engines. Sounds familiar, right?

Companies like Baker Electric, Detroit Electric, and Columbia Electric dominated the market. The Detroit Electric, for example, could travel 80 miles on a charge and was a favorite among doctors and executives. But these EVs had a major flaw: they were expensive. A Baker Electric cost around $2,000—roughly $60,000 today. The Model T, by contrast, started at $850 and eventually dropped to $300. Price, not performance, was the deciding factor for most buyers.

The Rise of the Gas Car (and the Fall of the EV)

So what killed the electric car in the 1910s? A few key developments:

- The electric starter: In 1912, Cadillac introduced a self-starting gas engine, eliminating the need for hand-cranking. This removed a major advantage of EVs.

- Cheap oil: The discovery of oil in Texas and California made gasoline abundant and affordable. By 1915, gas cost less than 10 cents a gallon—about $2.50 today.

- Roads and infrastructure: As the U.S. expanded, people needed cars that could travel long distances. Gas cars could go farther and refuel quickly, while EVs were limited by range and charging time.

- Ford’s production genius: The Model T’s assembly line slashed costs and boosted production. By 1914, Ford was making a car every 90 seconds. EVs couldn’t compete with that scale.

By 1920, electric cars had nearly disappeared from the market. The Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project was a casualty of this shift. Edison’s batteries were too heavy, Ford’s focus was elsewhere, and the world wasn’t ready for EVs yet. As one writer put it, “The electric car died not because it was a bad idea, but because the timing was wrong.”

The Technical Side: Why Edison’s Batteries Failed

The Promise of Nickel-Iron Batteries

Edison’s nickel-iron (Ni-Fe) battery was a game-changer in theory. Unlike lead-acid batteries, which degraded quickly, Ni-Fe batteries could last for decades. They were also more tolerant of overcharging and deep discharging, making them ideal for EVs. In fact, some of Edison’s batteries from the 1920s are still in use today—a testament to their durability.

But there was a catch. Ni-Fe batteries had two major drawbacks:

- Low energy density: They stored less energy per pound than lead-acid batteries. This meant heavier batteries for the same range.

- High cost: The materials and manufacturing process were expensive. A Ni-Fe battery for a car could cost as much as the car itself.

Edison knew these issues, but he was confident he could solve them. He spent years tweaking the design, even testing prototypes on his own car. By 1914, he claimed his batteries could deliver 100 miles of range. But when Ford tested them, the results were disappointing. The batteries added hundreds of pounds to the car, reducing performance and efficiency. And the cost? Far too high for Ford’s mass-market vision.

Lessons for Today’s EV Battery Tech

The story of Edison’s batteries holds a valuable lesson for modern EV development: progress isn’t linear. Just because a technology seems promising doesn’t mean it’s ready for prime time. Today’s lithium-ion batteries face similar challenges. They’re better than Ni-Fe batteries, but they’re still heavy, expensive, and resource-intensive to produce.

Here are a few practical takeaways:

- Range anxiety isn’t new: Drivers in 1914 worried about running out of juice, just like drivers do today. The solution? Better batteries and more charging stations.

- Cost matters: A $500 electric car was a pipe dream in 1914, just like a $25,000 EV is today. Innovation needs to be affordable to succeed.

- Durability is key: Edison’s batteries lasted decades, but today’s EVs often degrade after 10 years. Longer battery life could make EVs more appealing.

The good news? We’re closer than ever to solving these problems. Solid-state batteries, for example, could offer higher energy density and faster charging. And with more charging stations, range anxiety is fading fast. The Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project may have failed, but its spirit lives on in today’s EV revolution.

Why the Project Failed (And What It Teaches Us)

The Perfect Storm of Challenges

The Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project wasn’t just a technical failure—it was a victim of timing, economics, and market forces. Let’s break down why it didn’t work:

- Technology wasn’t ready: Batteries in 1914 couldn’t deliver the range, power, or affordability needed for mass adoption.

- Infrastructure was lacking: No charging stations, no home electricity in rural areas, and no standardized battery systems.

- Ford’s priorities shifted: The Model T was a runaway success, and Ford didn’t want to divert resources to a risky new project.

- Gas cars had momentum: Cheap oil, better roads, and the electric starter made gas cars the obvious choice for most buyers.

Edison himself admitted the project was ahead of its time. In a 1914 interview, he said, “We’re not ready for electric cars yet. But we will be.” He was right—just 100 years too early.

The Modern Parallel: EVs in the 2020s

The irony is that the same factors that doomed the Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project are now driving the modern EV revolution. Today’s EVs have better batteries, more charging stations, and government support. But the challenges are still there:

- Range and charging: While modern EVs can go 250-400 miles on a charge, charging times are still slower than refueling with gas.

- Cost: EVs are getting cheaper, but they’re still more expensive than gas cars in most cases.

- Consumer habits: Many people still prefer gas cars because they’re familiar and convenient.

The lesson? Innovation takes time. Edison and Ford were pioneers, but they were fighting against the status quo. Today’s EV makers are in the same position. The difference is that the world is finally ready for change.

Legacy: How Edison and Ford Shaped the Future of EVs

The Unfinished Dream

Although the Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project never reached mass production, it left a lasting legacy. Edison’s work on batteries laid the groundwork for future advancements, and Ford’s interest in EVs inspired generations of engineers. Even today, automakers like Tesla and Ford (with the Mach-E and F-150 Lightning) are revisiting the electric dream that Edison and Ford started.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the project is how it mirrors today’s EV challenges. Edison’s struggle to balance battery weight, cost, and range is eerily similar to the problems faced by modern engineers. And Ford’s focus on affordability and mass production is still the key to EV adoption. As Elon Musk said in 2016, “The goal is to make electric cars that are better, faster, and cheaper than gas cars.” Sound familiar?

The Data: Then vs. Now

Let’s compare the 1914 electric car landscape with today’s EV market:

| Metric | 1914 (Edison/Ford) | 2024 (Modern EVs) |

|---|---|---|

| Average range | 40-80 miles | 250-400 miles |

| Charging time | 12-24 hours (home) | 30 mins (DC fast charge) |

| Cost per vehicle | $2,000+ (Baker Electric) | $35,000+ (Chevy Bolt) |

| Charging stations | Almost none | Over 150,000 in U.S. |

| Market share | ~30% of cars | ~10% of new sales |

The progress is staggering. In just 100 years, EVs went from a niche technology to a mainstream option. And it’s not just cars—electric trucks, buses, and even planes are now in development. The Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project may have failed, but its vision is finally coming true.

The Road Ahead: What Edison and Ford Teach Us About Innovation

So what can we learn from the Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car story? First, innovation is never a straight line. Edison and Ford faced setbacks, but they kept pushing. Second, timing is everything. A great idea can fail if the world isn’t ready. And third, partnerships matter. Edison’s batteries and Ford’s production skills were a perfect match—just not in 1914.

Today, we’re living in the world Edison and Ford imagined. EVs are cleaner, quieter, and more efficient than gas cars. Charging networks are expanding. And battery technology is improving every year. The dream of a $500 electric car might still be out of reach, but the $30,000 EV is getting closer.

As we look to the future, let’s remember the pioneers who paved the way. Edison and Ford didn’t just build cars—they built a vision. And that vision is finally coming to life. The Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car revolution may have been delayed, but it’s here now. And it’s changing the world, one mile at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

What was the collaboration between Thomas Edison and Henry Ford for an electric car?

In the early 1910s, Thomas Edison and Henry Ford partnered to develop an affordable, efficient electric vehicle. Their goal was to combine Edison’s battery technology with Ford’s mass-production expertise, though the project was ultimately shelved due to limitations in battery range and the rise of cheap gasoline.

Why did the Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project fail?

The Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car project faced challenges like short battery life, high costs, and limited charging infrastructure. At the same time, the internal combustion engine became more practical, especially with Ford’s Model T dominating the market, making the electric alternative less viable.

Did Thomas Edison invent the first electric car with Henry Ford?

No, Edison and Ford didn’t invent the first electric car—early prototypes existed as far back as the 1800s. However, their collaboration aimed to create a mass-market version, leveraging Ford’s assembly lines and Edison’s nickel-iron batteries to revolutionize personal transportation.

What type of battery did Edison and Ford plan to use in their electric car?

They intended to use Edison’s nickel-iron (NiFe) batteries, which were more durable than lead-acid batteries of the time. While these batteries lasted longer, they were heavier and less energy-dense, contributing to the project’s eventual discontinuation.

How close was the Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car to production?

Ford and Edison built a prototype around 1914, but it never entered mass production. Despite promising tests, the car couldn’t match the range and convenience of gasoline vehicles, and the partnership shifted focus to other ventures.

Could the Edison-Ford electric car concept succeed today?

Modern advancements in battery tech, charging networks, and renewable energy make the core idea far more viable now. The Thomas Edison Henry Ford electric car vision was ahead of its time, but today’s EV market validates their ambition—albeit a century later.